"People are more motivated when they feel in control of their actions, rather than being directed by external forces."

Richard M. Ryan

Clinical Psychologist and Motivational Consultant

- Date

Why Dont My Team Members Work As Hard As I Do?

posted in Leadership

Adam Kreek

Welcome to Your Next Leadership Breakthrough

If you’ve ever wondered, "How do I get people motivated when they just don’t seem to care?" or "How do I inspire my team to step up and take action?"—you’re in the right place.

Over the past two decades, I’ve travelled the world as a leadership coach and consultant, sharing insights from my Olympic journey, my row across the Atlantic, and lessons from the hundreds of business teams and organizational leaders I've coached. And time after time, leaders come to me with the same question: “How do I get people to care as much as I do?” It’s one of the biggest frustrations in leadership—knowing exactly what needs to be done but feeling stuck because your team isn’t as fired up as you are.

This blog-booklet is designed to help you overcome that challenge. We’re going to explore how you can create the conditions that get people moving—whether it's building a sense of ownership, boosting confidence, or creating connections that inspire action. This booklet is about giving you practical tools to transform your leadership so your team can stop dragging their feet and start hitting their stride.

I constantly see this as one of the biggest challenges in leadership: We step into new roles, and we have to find ways to get people going—to spark that internal fire. So, I thought I’d pull from my history of rowing and lean on a metaphor loosely based on self-determination theory. Now, don’t let the name scare you—self-determination theory, originally developed by psychologists Ryan and Deci, offers a simple, understandable framework to grasp different levels and styles of motivation. We’ll be diving into fancy terms like "introjected regulation" (sounds academic, right?) but don’t worry. These words just help us understand the gradient of motivation, from externally driven to internally fueled.

Edward Deci and Richard Ryan were determined (pun intended) to figure out what really motivates people. Spoiler: it’s not just money or fear of punishment. They discovered that humans thrive when three basic needs are met—autonomy (having control), competence (feeling like you’re good at something), and relatedness (feeling connected to others). SDT has since become one of the top theories in understanding what drives us from the inside out. It's like they cracked the code on motivation, and now, leaders everywhere are using it to get better results without just dangling carrots.

Through the stories of Maggie, Sarah, and Mike, you’ll see how motivation is shaped by our need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Maggie’s journey shows us what happens when motivation is undermined. Sarah thrives when her basic psychological needs are nourished. And Mike? He’s the construction boss who’s bringing this theory to life in a tough, real-world environment.

So buckle up. This isn’t just about theory—it’s about real tools you can use to transform how you lead and how you think about motivation. And hey, if we get a few laughs along the way, even better. Ready to unlock the secrets of what truly drives you and your team? Let’s dive in!

Self-determination theory explains that motivation isn't just about external rewards or avoiding punishment. It's about satisfying three basic needs: autonomy (the feeling that you have control over your actions), competence (feeling capable of succeeding), and relatedness (feeling connected to others). When these needs are met, our motivation flourishes. When they’re undermined, motivation fizzles.

In this booklet, we'll explore three powerful stories:

- First, we’ll meet Maggie. She’s our case study on what happens when motivation is undermined. Think of it as motivation gone rogue, with external pressures pushing her further into frustration.

- Next, we turn to Sara—who finds herself on the opposite track. Her motivation skyrockets when her autonomy, competence, and relatedness are nourished.

- Finally, we’ll dig into Mike’s journey in a construction firm. How does self-determination theory apply in a real-world, blue-collar environment? Mike’s story will show us the practical side of motivation in action, with all its bumps and successes.

By the end of this, you’ll have a better understanding of how to recognize these motivational elements in your life and work—and maybe crack a joke or two along the way (because who said motivation theory has to be boring?)

Throughout this blog-booklet, you’ll come across sections labelled “Reflect on Your Leadership.” These are designed to be more than just a break in the reading—they’re your chance to stop, think, and apply what you’ve just read to your own leadership style. The goal here is to help you connect the dots between the theory we’re exploring and the way you lead, manage, and interact with your team.

Each reflection section will ask you targeted questions to help you consider how the principles of self-determination theory are playing out in your own world. Are you fostering an environment that encourages autonomy, competence, and relatedness? Or are there gaps that could be undermining your team’s motivation? These sections will guide you through that thinking process.

This isn’t about getting the "right" answers—it’s about taking the time to self-assess. I encourage you to pause, reflect, and even jot down your thoughts. The more you engage with these questions, the more you’ll start to see how small adjustments can lead to big changes in how your team operates, how they’re motivated, and ultimately, how they perform.

So when you hit a "Reflect on Your Leadership" section, take a moment. These reflections are designed to help you grow as a leader and bring these concepts from theory into practice. Ready to dive deeper? Let’s do this!

What is Self-Determination?

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is all about what really gets us out of bed in the morning—besides coffee. It says that humans have three main motivational needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

- Autonomy is the sense that you're in control of your life, not just following orders like a robot. Think: "I choose to eat this salad," not "My diet app made me do it."

- Competence is feeling confident in your abilities. We all want to crush it, not just survive the day without spilling coffee on our shirt.

- Relatedness is the warm, fuzzy feeling we get when we're connected to others. Like when someone laughs at your jokes or at least pretends to.

When these three needs are met, motivation soars. When they're not, you're stuck staring at your to-do list like it’s written in hieroglyphics.

In short, SDT is about giving us the right ingredients for motivation. And no, it doesn’t come with a free motivational poster.

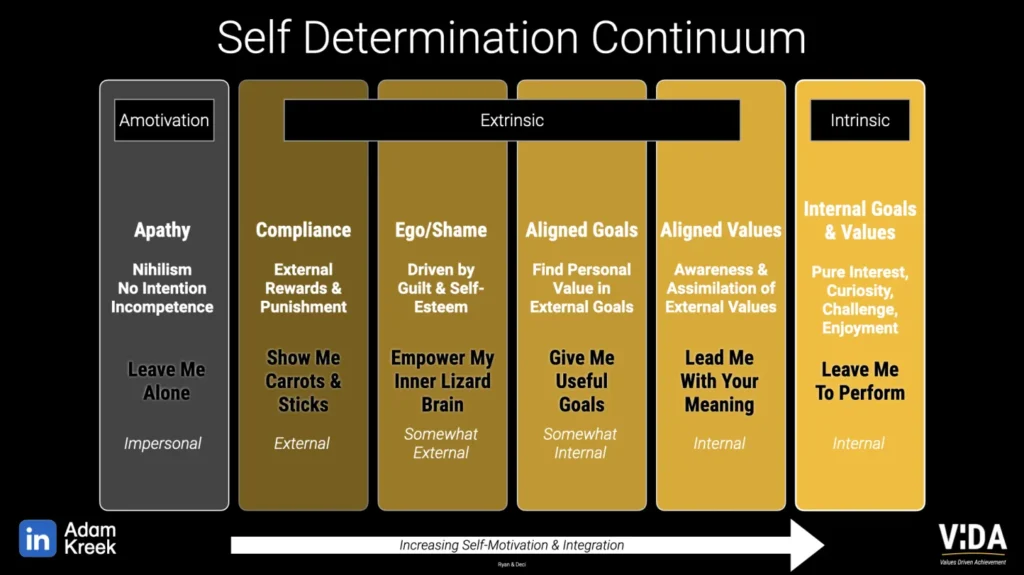

Most people try to motivate by pushing harder. What if we flipped the script—and pulled? The Self-Determination Theory (SDT) Continuum offers a practical map of human motivation, from external pressure to deeply internal drive. I’ll walk you through the model below, and show how you can use it to shift your team—and yourself—into action that actually sticks.

Alright, let’s reframe this whole motivation spectrum through the lens of leadership and management. Here’s the deal: Amotivation—that’s the one place you don’t want your team to be. It’s the black hole of motivation. But as we move up the scale, there’s a lot we can work with as leaders, especially if we’re smart about emotional and systems awareness.

Amotivation (Non-Regulation)

Leave me alone!

Let’s start at the bottom. This is where someone is so disconnected that they’re not even trying. There’s no drive, no direction, no sense of purpose. As a leader, this is the danger zone. No amount of incentives or speeches will light a fire here because the person has no reason to engage. They’re just going through the motions (or worse, they’ve stopped moving altogether). The goal here is to reconnect them with some basic sense of meaning or value—because, let’s face it, we can’t lead a stationary bike.

External Regulation

Use Carrots and Sticks

Now, we step up to external regulation. Here, your people are motivated by rewards or punishments. It’s the "I’ll do it if I get paid more" or "I’ll avoid it because I don’t want to get yelled at" vibe. This can get results, but it’s not sustainable in the long run. It’s like running on a treadmill that someone else controls—it works, but only as long as they keep cranking the dial. Great leaders can tap into this, but they must also understand that without some emotional connection, the moment the carrot or stick disappears, so does the motivation.

Introjected Regulation

Use Guilt, Shame and the Lizard Brain

Here, we start getting into the emotional game. Introjected regulation means the motivation is internal, but it's fueled by feelings like guilt or shame. People do things because they feel they have to, not because they want to. This is where emotional awareness from leaders is crucial. You want to be sure your team isn’t just hustling out of fear of disappointing others or themselves. By honouring their basic need for relatedness and competence, you can turn this guilt-driven action into something healthier, more productive, and lasting.

Identified Regulation

Create Goals Alongside the People You Lead

Now we’re talking! Identified regulation is when people see the value in what they’re doing, even if it’s not their favourite task. Leaders who can connect tasks with individual goals and values are gold. When someone understands, “Hey, this isn’t fun, but it’s important because it gets me closer to something I care about,” you’ve struck a balance between external demands and internal buy-in. Leaders here honour the need for competence by showing how the work fits into the bigger picture.

Integrated Regulation

Align The People You Lead with Your Values and Purpose

Here’s where it all starts to hum. Integrated regulation means your people are doing something because it aligns with their personal values. As a leader, your job is to keep fostering that connection between the task and their core beliefs. When people feel like their work is part of who they are, they move beyond just "doing the job" to owning it. You honour their need for autonomy here by showing them how their work fits into their identity. This is where the magic happens.

Intrinsic Regulation

Empower Your Team And Leave Them To Perform

And then we hit the sweet spot: intrinsic regulation. At this point, motivation is pure. People do things simply because they love them. They find joy, challenge, and meaning in the work itself. For leaders, your role is to create the space where people can tap into this naturally—honouring their autonomy, competence, and relatedness in a way that keeps that intrinsic fire burning.

In short, the further up the motivation scale you go, the more you need to honour those basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—to unlock the highest levels of engagement and effectiveness. The more emotionally and system-aware you are as a leader, the better you can leverage each form of motivation to get the best out of your team, wherever they fall on the scale.

Dig Deeper. Three Stories

Understanding motivation is like trying to crack the code of the human brain—it’s complex, messy, and utterly fascinating. But here’s the thing: when you finally figure out how motivation really works, it’s a game-changer. You can radically shift the way you lead, improve how you work, and even transform your everyday life. It’s not just about getting people to do things; it’s about tapping into what drives them deep down. When you unlock that code, everything starts to fall into place.

So, what happens when motivation goes haywire? Well, enter Maggie—our case study in what can go horribly wrong when motivation is undermined at every turn. It’s a story of frustration, disconnection, and, yes, a little bit of hope. Stick with us, because from Maggie’s cautionary tale, we’ll shift gears to Sara, a woman whose motivation blooms when the right psychological needs are met. Finally, we’ll roll up our sleeves with Mike, a guy in the construction world who shows us what motivation looks like when you build the proper foundation. These stories will help you see how this motivation stuff plays out in the real world, so let’s dig in!

Maggie’s Story: Motivation Undermined

Maggie is an athlete caught between two worlds—the synchronized dance of rowing in an eight and the lonely grind of a single scull. For her, rowing is more than just a sport. It’s a sanctuary where she feels in control, powerful, and connected to the water. But lately, things haven’t been going so smoothly. Her motivation, once a strong current pulling her forward, has been slowly drained by the very people and environment that are supposed to lift her up.

At the rowing club, Maggie’s coach seems to have mastered the art of demotivation. Feedback is sparse, and when it comes, it’s laced with sarcasm or flat-out criticism. Instead of celebrating small victories or offering constructive advice, her coach nitpicks at every mistake. The constant barrage of negativity leaves Maggie questioning her abilities, eroding her confidence. The joy of rowing—the feeling of being in sync with the boat, the water, her own body—has been overshadowed by the looming fear of failure and the coach's unrelenting judgment.

It doesn’t stop there. Her teammates, instead of fostering camaraderie, seem to thrive on competition to the point of toxicity. Cliques dominate the boathouse. There’s a palpable sense of "every rower for themselves." Maggie feels like an outsider, not quite fitting in with the inner circle. She finds herself rowing harder, not out of passion, but out of a desperate need to prove she belongs—yet it never seems enough. Her eight's once harmonious rowing rhythm has become a battlefield of egos.

In her single scull, where Maggie once found solace, even that has lost its spark. Without the support and encouragement of a team or coach, she feels isolated. Her once-therapeutic solo rows have turned into lonely slogs where her internal voice mimics the harsh criticisms of her coach. She’s lost her sense of autonomy, her confidence shattered, and her love for rowing dwindles with every stroke.

Maggie’s motivation has been undermined on all fronts. Her need for competence is dismissed with negative feedback, her need for relatedness is crushed by the exclusionary behaviour of her teammates, and her need for autonomy is stifled by the rigid control of her coach. She’s rowing, but it feels like she’s constantly fighting an upstream battle.

This is Maggie’s story—an extreme example of what happens when motivation is sabotaged. But stick with me because next we’ll shift to Sara, whose story shows us what happens when motivation is cultivated, nurtured, and allowed to flourish. If Maggie’s rowing journey is a cautionary tale, Sara’s is a hopeful roadmap. Stay tuned.

Amotivation (Apathy, Going Through the Motions)

Maggie shows up to practice, but her heart isn’t in it. Her coach rarely gives her feedback, and she feels like no one notices whether she’s improving or not. She rows because it’s expected, but she doesn’t have any internal or external motivation to push herself. She often feels like she’s just going through the motions, questioning why she even bothers.

- Competence: Maggie feels her skills are not recognized or improved upon, leading to a lack of competence.

- Relatedness: The team dynamic is cliquey, and she doesn’t feel like she belongs, further driving her amotivation.

External Regulation (Rewards, Punishments)

Maggie’s coach primarily motivates through external rewards and punishments. She’s told she’ll be benched if her times don’t improve, and the focus is always on winning medals rather than personal growth. Maggie rows because she doesn’t want to face the consequences of letting the team down, but there’s no joy or personal investment.

- Autonomy: Maggie feels controlled, with no say in her training. Her autonomy is undermined by constant deadlines and threats.

- Competence: Instead of receiving constructive feedback, Maggie only hears from her coach when she’s not performing well, leading to negative feelings about her skills.

Introjected Regulation (Guilt, Compulsion)

Maggie often feels guilty when she doesn’t row well, as her coach makes her feel like she’s letting everyone down. She’s driven by a sense of obligation and fear of judgment. There’s no internal satisfaction—just pressure to avoid feeling bad about herself.

- Relatedness: Her sense of relatedness is weakened, as her coach’s criticism feels like personal attacks, rather than constructive guidance. Maggie feels isolated rather than supported.

Identified Regulation (Consciously Valued Goals)

Though Maggie values fitness and discipline, she’s lost sight of how rowing aligns with those goals. She knows it should, but the constant external pressure and lack of personal fulfillment have made it difficult for her to see rowing as a part of her personal growth journey.

- Competence: Maggie rarely feels competent because her coach doesn’t provide positive feedback or encouragement.

Integrated Regulation (Values Fully Assimilated into Self)

Maggie struggles to integrate rowing into her identity. The toxic team culture and lack of support make it hard for her to feel like rowing is truly part of who she is. She might value fitness and teamwork in theory, but her experience at the club has made it hard for her to internalize those values in relation to rowing.

- Relatedness: Maggie feels disconnected from the team and the sport itself, making it difficult to integrate rowing into her identity.

Intrinsic Regulation (Pure Enjoyment)

Sadly, Maggie rarely experiences intrinsic regulation. She used to enjoy rowing, but the constant external pressures and lack of support have drained the joy out of it. While she occasionally remembers why she started rowing, those moments are fleeting, and her environment doesn’t support her reconnecting with that intrinsic love for the sport.

- Autonomy: Maggie feels controlled by her coach, leaving her no room to explore or rediscover her personal love for rowing.

Maggie’s Reflections

Let me break it down for you. Maggie is stuck in the rowing equivalent of motivational quicksand. She shows up to practice, sure, but it’s more like she’s showing up to a dentist appointment—she’s there because she has to be, not because she wants to be. Her coach, bless his heart, couldn’t motivate a dog to chase a ball. Feedback? Only if you count criticism as feedback. When Maggie does hear from him, it’s mostly to tell her what she’s doing wrong, which has become a running theme.

Her sense of competence? Shot. She doesn’t feel like she’s improving, and honestly, no one is acknowledging whether she is or isn’t. Then, there’s the team dynamic, which feels more like high school cafeteria politics than a synchronized rowing team. Cliques have formed, and Maggie feels like the odd one out. Instead of bonding with her teammates, she’s stuck on the outside looking in—about as related as a pair of mismatched socks.

Motivational tactics from her coach include the usual grab bag of threats and promises, mostly focused on times, medals, and not embarrassing the club. Autonomy? She hasn’t had a taste of that since the first day she picked up an oar. If Maggie doesn’t perform, she gets benched. If she does, it’s on to the next race with zero acknowledgment. Personal growth? What’s that? She’s rowing purely out of obligation at this point, motivated by guilt, the fear of failure, and not much else.

At one point, Maggie valued fitness and discipline, and rowing seemed to align with those goals. But now? The joy is gone, replaced by a feeling that she’s just a cog in a wheel that’s spinning in circles. She doesn’t feel like rowing is part of who she is anymore, just something she has to do. Her identity is disconnected from the sport, and the more toxic the environment gets, the further she drifts from any intrinsic motivation she might have had in the past. Maggie, unfortunately, is the poster child for amotivation—floating along with no real purpose, no joy, and no connection.

But not all is lost, my friend. Let’s take a hard left and meet Sara, whose motivation is like a breath of fresh air compared to Maggie’s stifling environment. Sara is thriving because the people around her understand what makes her tick. They honour her basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Stick around to see how Sara's story flips the script and shows us what happens when motivation gets the nurturing it needs. Spoiler alert: it’s a lot better than rowing in quicksand.

Sara’s Story: Motivation Enhanced

Sara has been a dedicated rower for years, splitting her time between the camaraderie of the eight and the solo challenge of the single scull. For her, rowing isn’t just about competition or keeping fit—it’s about balance. She thrives in the mix of team effort and personal mastery. And it shows. Her motivation is like a well-oiled machine, running smoothly because the people around her, from her coach to her teammates, understand what truly drives her.

Let’s start with competence—Sara feels like she’s constantly growing. Her coach strikes that perfect balance between pushing her to improve and acknowledging her progress. She doesn’t just hear about what needs fixing; she gets constructive feedback that helps her tweak her technique in meaningful ways. After every practice, she walks away feeling a little bit stronger, a little more skilled. That sense of mastery fuels her desire to keep coming back for more. It’s not just about winning races—it’s about getting better every single day.

Then there’s relatedness. In the eight, Sara thrives on the trust and connection with her teammates. It’s not just about pulling together physically—it’s about being in sync emotionally, too. The team dynamic is inclusive and supportive, with everyone lifting each other up, rather than competing for attention or approval. Whether it’s cracking jokes before practice or debriefing after a tough race, Sara feels like she belongs. There’s no clique drama here, just genuine camaraderie that makes showing up to the boathouse something she looks forward to. She’s not just part of a team—she’s part of a community.

Now, let’s talk about autonomy. Sara’s coach understands that while guidance is crucial, so is giving athletes the space to take ownership of their training. Instead of micromanaging every stroke, her coach encourages her to set personal goals and explore her own approach to rowing. When Sara rows in her single scull, she relishes the freedom it offers. There’s no one else in the boat but her—it’s just her, the water, and the rhythm of her oars slicing through the surface. Her coach knows when to step back and let Sara find her own flow. That kind of freedom builds trust, not just between coach and athlete, but within Sara herself. She feels empowered to make decisions about her training and confident in her abilities.

And the result? Sara rows because she loves it. She’s not out there because she has to be or because she’s afraid of letting someone down. She rows because it’s a part of who she is—both as an athlete and as a person. The intrinsic motivation is undeniable. On the water, whether she’s with her team or rowing solo, Sara feels alive, energized, and connected to something bigger than herself. Rowing isn’t just an activity—it’s a reflection of her identity. She’s motivated by her own internal drive, supported by a culture that respects her needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

So, while Maggie’s story was a cautionary tale of how motivation can be drained, Sara shows us what’s possible when those basic psychological needs are not only met but embraced. The difference is like night and day, or more fittingly, like rowing through choppy waters versus gliding across a calm lake.

But hold up—after we haul on Sara’s oars, we’ve got one more tale to explore. Enter Mike, the guy who works in construction. You might think motivation plays out differently in the workplace, but spoiler alert—it doesn’t. Mike’s story will show us how these same principles of motivation come into play in a completely different world. After Sara’s story, we’ll see how Mike’s construction site stacks up against Sara’s rowing club.

Sara’s motivational is a masterclass in how things should go, while Maggie’s experience, well… let’s just say it’s the cautionary tale. For Sara, we start at the pinnacle: intrinsic regulation. Contrast this with Maggie, who started her journey in the muck of amotivation—showing up, but with her heart long checked out. While Maggie had to claw her way up from the bottom, showing us the full spectrum of motivation from least powerful to most, Sara’s story moves from the most potent motivation, intrinsic regulation, down the scale. It finishes with ways a coach can help her when Sara flirts with amotivation.

Intrinsic Regulation (Pure Interest and Enjoyment)

When Sara rows in the single scull early in the morning for her Zone 2 training, she feels pure joy. She’s not thinking about times or races—she’s simply in sync with the water and her body. Her coach knows she enjoys these sessions and encourages her to take time for them, reminding her that it’s about feeling connected to the sport she loves. This builds her autonomy—Sara feels fully in control of her rowing decisions, allowing her intrinsic motivation to flourish.

- Autonomy: Her coach gives her the freedom to structure some of her own sessions, trusting that she will push herself because she loves the feeling of rowing.

- Competence: Consistent improvements in her skills, abilities, and performance are incredibly motivating. As she refines the finer points of her sculling and rowing, her passion for the sport and all its challenges increases.

- Relatedness: When Sara talks about her morning rows, her teammates and coach listen with enthusiasm, sharing her joy. This reinforces her sense of belonging. Although she is often rowing alone, Sara is connected to something bigger than herself. She feels a sense of presence, oneness and purpose.

Intrinsic regulation is the nirvana of motivation. You’re not chasing medals, praise, or paychecks—you're doing it for the pure, unadulterated joy of the thing itself. It’s the ultimate “I do this because I love it” mindset. In Self-Determination Theory (SDT), intrinsic motivation is when the activity is the reward. You’re in it because it aligns with your deepest interests and brings you joy—no external validation needed.

At this level, it’s not about what others think or any external outcomes. You’re rowing, writing, painting, or whatever floats your boat (pun intended) simply because it feels good. You get into flow states, lose track of time, and find deep satisfaction in just doing. It’s like going for a run, not because you want to lose weight, but because you love the feeling of your feet hitting the pavement and the wind in your hair. The activity itself becomes the prize.

At the core, intrinsic regulation makes you feel connected to something larger than achievement. It’s why athletes get up at 5 AM to train when no one is watching, and why writers write for hours on end, knowing most of their words will never see the light of day. You’re not looking for external rewards; the act itself is all the reward you need.

You As The Coach?

Now, imagine yourself as the coach. You’re not just leading practice—you’re guiding your athletes or team members to connect with the sheer joy of their work. As the coach, your role isn’t simply about refining technique or setting targets; it’s about helping Sara (or anyone you lead) rediscover why they fell in love with the sport in the first place. You’re there to remind them that rowing isn’t just a means to an end; it’s something that brings joy, satisfaction, and a sense of inner peace.

Think about how you coach with intrinsic regulation in mind. You’re not pushing them to win medals or hit metrics alone—you’re creating an environment where they find fulfillment in the process itself. It’s about fostering a mindset where rowing, or any task, becomes an act of personal joy, not just performance. When you emphasize intrinsic motivation, you’re helping your team reconnect with the simple love of the game—the love that got them started. The rhythm of the strokes, the calm of the morning water, the personal satisfaction of getting better just for the sake of it—that’s the power of intrinsic motivation.

As a leader, you have the opportunity to shape this mindset. You’re not just helping them complete tasks or hit goals; you’re reminding them why they’re doing it in the first place. By doing this, you help them see the value in the work itself. When they find joy in what they do, they’re no longer just rowing for the race—they’re rowing because it brings them to life. That’s the power of intrinsic motivation: making the process itself the reward.

This is where your leadership becomes transformational. As you read through the next section, think about how you can inspire those you lead to connect their work to their inner joy and personal satisfaction. This isn’t just about hitting numbers; it’s about any project, any passion, any team. Let’s dive into how you can make the journey as rewarding as the destination!

Ways a coach might use integrated regulation to motivate Sara:

- Linking rowing to Sara’s passion: As the coach, you can help Sara reconnect with the joy and love she has for rowing, beyond the metrics and external achievements. It’s about showing her that rowing is an activity that aligns with her natural interests and what truly excites her.

- Example: “Rowing isn’t just something you’re good at—it’s something you love doing. Every stroke on the water is a chance for you to connect with the energy and peace that rowing brings you.”

- Connecting rowing to personal fulfillment: You can emphasize how rowing brings Sara a sense of satisfaction that transcends competition. Help her see that rowing satisfies something deeper inside her, making the practice itself the reward.

- Example: “When you row, it’s more than just about winning—it’s about the sense of fulfillment you get from pushing your limits and enjoying the process. Rowing fills your cup.”

- Making rowing a tool for mindfulness and flow: As her coach, guide Sara to use rowing as a meditative practice where she can enter a state of flow. In these moments, she’s completely immersed in the activity, losing track of time and becoming one with the experience.

- Example: “When you’re out on the water, you’re fully present, every stroke in tune with the boat and the rhythm of the water. Rowing gives you a rare chance to just be in the moment.”

- Framing rowing as a reflection of her best self: Help Sara understand that rowing is an expression of her most authentic self. It’s not just something she does—it’s part of who she is. Her dedication, focus, and effort in rowing mirror her deeper values.

- Example: “Your determination and focus out there on the water are reflections of your inner strength. Rowing shows you exactly who you are—driven, resilient, and powerful.”

- Positioning rowing as a holistic practice: Show Sara how rowing fits into her overall well-being. It’s not just physical exercise; it’s a mental and emotional anchor that keeps her grounded and balanced in life.

- Example: “Rowing isn’t just about keeping fit; it’s a way for you to stay mentally strong, emotionally balanced, and connected to yourself. It’s part of how you keep your whole life in harmony.”

Reflect on your leadership:

As a leader, your role isn’t just about hitting targets or keeping things on track. It’s about helping the people you lead, like Sara, find true connection to their work. Sure, there will always be tasks and deadlines, but the real magic happens when your team sees their work as more than just a to-do list. You want them to feel that what they’re doing reflects who they are, what they value, and where they’re headed. When people connect their work to something intrinsic, they find purpose in the everyday grind—and that’s when you unlock the highest level of motivation and fulfillment. You’re not just managing; you’re empowering them to align their work with their identity and aspirations.

Think about the impact this has, not just on performance but on the culture you’re building. When people feel that their work is an extension of their true selves, they’re more engaged, more creative, and, frankly, happier. And let’s face it—when your team thrives on that deeper connection, your job becomes more fulfilling too. You’re not just checking off boxes or enforcing deadlines; you’re creating an environment where people grow, live authentically, and bring their best selves to the table.

Think about these questions as you reflect, or journal them:

- How does guiding your team to connect their work with their core values enhance your own sense of purpose as a leader? What satisfaction do you gain from this deeper, more impactful way of leading?

- How can building a culture where work feels personally meaningful create a lasting positive impact? What ripple effects do you see in your team’s lives and the broader influence your organization has? What legacy are you creating by leading in a way that empowers people to live their values?

Key Points of Intrinsic Regulation:

- Intrinsic regulation occurs when the behaviour is driven purely by the enjoyment and satisfaction of the activity itself, with no need for external rewards or outcomes.

- The individual engages in the activity because it aligns with their interests, passions, and natural curiosities, making the process itself fulfilling and enjoyable.

- It creates a deep sense of personal connection and flow, where the person becomes fully absorbed in the activity, losing track of time and experiencing a heightened sense of fulfillment.

- Intrinsic regulation represents the most autonomous form of motivation, where the individual feels completely in control and acts out of a genuine love for the activity, rather than any external pressures or goals.

Integrated Regulation (Values Fully Integrated)

Sara’s values of discipline, fitness, and mental strength align perfectly with rowing. Now imagine how rowing embodies these traits and supports her growth as a person, not just as an athlete. Sara feels that rowing is an extension of who she is, rather than just an activity she participates in.

- Autonomy: The alignment between rowing and her core values strengthens her sense of autonomy. She’s not just rowing because of external pressures but because it fits with her life’s purpose.

- Relatedness: Sara is part of a club that emphasizes respect and personal growth, enhancing her feeling of belonging and relatedness.

Integrated Regulation is like the Jedi Master of extrinsic motivation—it’s got all the power but with way more internal control. It’s the most autonomous form of extrinsic motivation in Self-Determination Theory (SDT). In this level of motivation, a person not only gets why a behaviour is important, but it becomes a core part of who they are. They both identify and integrate their behaviour into their sense of self.

It’s no longer just something they do because someone else told them to. Nope, they’re doing it because it lines up with their values, goals, and identity. It’s like the difference between wearing a uniform because it’s required and wearing it because you are the uniform. You’re still working toward an external goal (like winning that race or crushing that project), but it feels like intrinsic motivation because the behaviour is now fully you. You’re rowing not just for the medal, but because rowing is what makes you, well… you.

You As The Coach?

Now, imagine yourself as the coach. You’re not just leading practice—you’re shaping motivation, helping your athletes or team members find deeper connections to their work. As the coach, your role goes beyond just giving instructions or setting goals. You’re having conversations that help Sara (or anyone you lead) see rowing as part of who she is, not just something she does to reach a goal.

Think about your current leadership, applying integrated regulation to your team. You’re not just helping them see the value of their work—you’re helping them become the work. It’s about connecting their tasks to their core values and making their role an extension of who they are. You’re showing them that what they do isn’t just a means to an end; it’s aligned with their identity, their principles, and their bigger life goals. As the leader, you’re helping them integrate their work into their sense of self, so it feels natural and meaningful. They’re not just doing the job to hit targets; they’re doing it because it reflects who they are and what they stand for. That’s the power of integrated regulation: making the work personal.

This is where you can make a real impact. As you read through the next section, step into that role—think about how you can use these forms of motivation in your own leadership. Don’t just skim it—underline phrases, jot down methods, and write down what resonates. Think about the people you lead. How can you inspire them to connect their work to their core values and identity? This isn’t just about rowing. It’s about any team, any project, any goal. Let’s dive in!

Ways a coach might use integrated regulation to motivate Sara:

- Linking rowing to Sara’s identity: As the coach, you might help Sara see rowing as part of who she is—not just something she does to achieve a goal but as an activity that reflects her core values and sense of self.

- Example: “Rowing is more than just a sport for you—it’s a way for you to live out your values of discipline, strength, and perseverance.”

- Connecting to life goals and self-concept: As the coach, you might help emphasize how rowing is integrated into Sara’s larger life goals, making it an essential part of her life journey, not just a separate task.

- Example: “You’ve built your life around staying healthy, challenging yourself, and continuously improving. Rowing fits perfectly with who you are and your vision for your future.”

- Fostering a deep personal connection: As the coach, you might help Sara reflect on how rowing resonates with her deepest values, making her feel that it’s not just about achieving goals but about living authentically.

- Example: “The discipline you’ve developed through rowing is something that defines you, whether in sports, work, or life. It’s a reflection of the person you want to be.”

- Framing rowing as part of her life’s purpose: As the coach, you might encourage Sara to see how rowing fits into her broader sense of purpose, helping her connect it to a vision she has for herself.

- Example: “Rowing helps you stay grounded and focused—it’s part of your journey to becoming the best version of yourself. It aligns with everything you stand for.”

- Making rowing a holistic part of her lifestyle: As the coach, you could show Sara how rowing contributes to multiple aspects of her life—physical, mental, and emotional health—demonstrating that it’s more than just training but part of her entire way of living.

- Example: “For you, rowing is not just about fitness; it’s about mental toughness, focus, and personal balance. It’s part of a lifestyle that keeps you fulfilled and balanced.”

Reflect on your leadership:

As a leader, your job isn’t just to check off boxes and make sure deadlines are met—it’s to help the people you lead, like Sara, connect their work to something deeper. Sure, everyone has tasks to do, but you want your team to see their work as more than a to-do list; you want them to see it as an expression of their values, identity, and ambitions. Help them realize that what they do today lines up with where they want to go tomorrow. By doing this, you’re not just boosting performance, you're creating a culture where people live authentically and find true fulfillment in their work. And let’s be real, when work feels like an extension of who they are, not just another day at the office, everyone’s happier—including you. Plus, these kinds of meaningful conversations? They’re the real secret to unlocking deeper growth and connection.

Think about the questions below, or journal them:

- How does supporting your team in connecting their work to their core values and aspirations align with your own purpose as a leader? What deeper sense of fulfillment can you gain by helping others grow in this way?

- How can fostering an environment where your team feels personally connected to their work create a positive ripple effect—both in their lives and the broader impact your organization has on the world? What legacy are you building by empowering others to thrive?

Key Points of Integrated Regulation:

- Integrated regulation occurs when behaviours are fully assimilated into one’s sense of self and identity, creating a strong sense of personal congruence and autonomy.

- The behaviour aligns with the person’s core values and long-term life goals, even though it’s still extrinsically motivated (because the person is working toward a specific outcome).

- It creates a deep, authentic connection to the behaviour, where the individual feels that engaging in it is an expression of who they are.

- It’s the closest form of extrinsic motivation to intrinsic motivation, as the individual feels a high level of ownership over their actions.

Identified Regulation (Consciously Valued Goals)

Sara is training for a big race, not because of external rewards, but because she values the challenge. She knows that the discipline and focus required for rowing will help her in other aspects of life. As her coach, you might emphasize the purpose of the race—how it helps her build resilience. Sara chooses this goal because she values the outcome, but it’s still an extrinsic motivator.

- Competence: Sara’s coach gives her positive performance feedback, helping her see how much she’s improving, and reminding her that this progress comes from her own commitment.

- Relatedness: Her teammates cheer her on during practice, making her feel supported in the pursuit of her goal.

Identified regulation is like the motivational apprentice—it’s not at the Jedi Master level yet, but it’s getting there. In Self-Determination Theory (SDT), identified regulation means that you get why something is important, and even if it’s not your favourite thing in the world, you’re choosing to do it because it aligns with your goals. The motivation is still extrinsic—you’re aiming for an external goal—but you’ve consciously decided it’s worth your time because it fits with your values and who you’re trying to become.

It’s like going for a run, not because you love running (spoiler: you don’t), but because you know it’s going to get you closer to the fitness level you want. You’re not just going through the motions because someone said you have to. Nope, you’re doing it because you’ve decided it’s important to your own progress. It’s the difference between clocking in at work to pay the bills and showing up because you know it’s part of the bigger picture you’ve set for yourself. You’re not just rowing for the finish line—you’re rowing because you know it’s moving you closer to where you want to be.

You as the coach?

Now, picture yourself as the leader, guiding your team through identified regulation. It’s not about getting them to love every task—let’s be real, they won’t. Your job is to help them see how their work fits into the bigger picture of their own career goals and personal development. Maybe they don’t enjoy every project, but if they understand how it’s moving them toward the promotion, skill set, or impact they want, they’ll stay engaged. As the leader, you’re connecting the dots between today’s tasks and tomorrow’s success. You’re making it clear that it’s not just about completing assignments—it’s about how those assignments drive them toward becoming the person and professional they want to be. That’s the beauty of identified regulation: showing the “why” behind the work.

Ways a coach might use identified regulation to motivate Sara:

- Emphasizing personal goals: As the coach, you could help Sara see how rowing aligns with her personal values and long-term objectives, encouraging her to engage in it because she believes it’s important.

- Example: “Sara, I know you care about staying healthy and pushing your limits. Rowing consistently will help you achieve those personal goals.”

- Highlighting future benefits: As the coach, you could explain how Sara’s current efforts will benefit her in the future, helping her see rowing as part of a larger personal growth plan.

- Example: “Training hard now will help you develop the discipline and resilience you’ll need for any future challenges, in rowing or in life.”

- Connecting the activity to meaningful outcomes: As the coach, you could show Sara how rowing contributes to something she values, such as teamwork, personal development, or even larger societal or environmental causes.

- Example: “Rowing teaches you patience, focus, and collaboration, all of which will help you in other areas of life—whether it’s school, work, or personal relationships.”

- Encouraging ownership of the process: As the coach, you might encourage Sara to take ownership of her training and decision-making process by recognizing how rowing fits into her broader sense of self and purpose.

- Example: “You’re someone who always strives to improve. Rowing is a way for you to live out that commitment to personal growth and excellence.”

- Focusing on personal fulfillment: As the coach, you could appeal to Sara’s desire to feel fulfilled by aligning rowing with her self-identity and personal sense of accomplishment.

- Example: “You’ve told me you’re proud of what you’ve accomplished so far in rowing. Staying committed will allow you to keep achieving the things you’re proud of.”

Reflect on your leadership:

As a leader, your role goes beyond making sure tasks are completed—it’s about helping your team find personal meaning in their work. With identified regulation, you’re guiding those you lead, like Sara, to see their daily responsibilities not just as boxes to tick, but as steps toward their larger personal and professional goals. They may not always enjoy every task, but they’ll recognize how it aligns with their bigger ambitions. By helping them consciously connect their work with their values and long-term objectives, you’re fostering a culture of purpose and progress. For you, as a leader, this isn’t just about getting things done—it’s about finding deeper satisfaction in seeing your team grow, succeed, and become more fulfilled in the process.

Think about the questions below, or journal them:

- How might helping your team connect their work to their long-term goals bring more meaning to your own role as a leader? What personal fulfillment could you gain by playing a crucial part in their growth and success?

- In what ways could guiding your team through this process of aligning their tasks with their values benefit your leadership outcomes, both in terms of performance and building stronger, more engaged relationships within your organization?

Key Points of Identified Regulation:

- It’s still extrinsic because the behaviour is motivated by external goals (e.g., health, self-improvement), but the individual identifies with these goals and believes they’re important.

- There’s a sense of choice and personal endorsement of the behaviour, making it more sustainable than purely externally controlled motivation (like external regulation).

- Identified regulation helps foster a sense of autonomy, as Sara would engage in rowing because it aligns with her personal values or long-term goals, even if rowing itself isn’t inherently fun.

Introjected Regulation (Guilt, Obligation)

Sometimes, when Sara is tired, she feels a slight internal pressure to attend practice because she would feel guilty if she let her team down. Though she enjoys rowing, she’s not always motivated purely by joy. She knows her team relies on her in the eight, and she feels obligated to show up.

- Relatedness: The strong bonds within her team are the source of her obligation, but it’s positive. She wants to be there for them, and they, in turn, show up for her. This sense of caring is key to keeping her motivation strong.

Introjected Regulation is like the middle child of motivation—it’s not the youngest getting all the attention (extrinsic), but it’s not the fully mature, self-driven motivation either. With introjected regulation, you’re doing things because you feel like you should or must, not because you truly want to. There’s that nagging internal voice saying, “If you don’t do this, you’ll feel guilty,” or, “You need to keep your self-worth intact, so don’t mess this up.”

It’s not fully external, like chasing a reward, but it’s not totally internalized either. You’re driven by pressure—whether it’s avoiding guilt, seeking approval, or keeping your pride intact. It’s like wearing a uniform because you’re afraid of letting others down if you don’t. You’re doing the task, not because it’s part of who you are, but because not doing it feels wrong or disappointing. It works, but it’s a little shaky—it’s motivation with a bit of a guilt trip.

You as the coach?

Now, picture yourself as the leader using introjected regulation to motivate your team. Here, you’re tapping into their internal pressure—the guilt, the sense of duty, or the need for approval. It’s not the most sustainable form of motivation, but it can be useful in the short term. You’re motivating them by reminding them of their responsibilities or how others are counting on them. It’s like nudging them with, “You don’t want to let the team down, do you?” or appealing to their sense of pride. As the leader, you’re leveraging their internal drive to meet expectations, even if it’s driven by the need to avoid guilt or failure. Just be mindful: while it works in a pinch, you don’t want to rely on it too often—it’s a fine line between motivation and burnout.

Ways a coach might use introjection to motivate Sara:

- Appealing to guilt or obligation: As the coach, you might remind Sara of how important it is to be consistent in her training and emphasize how she’d feel guilty or regretful if she didn’t put in the effort.

- Example: “You’ve worked so hard to get to this point—don’t let yourself down by skipping practice. Imagine how disappointed you’ll feel if you don’t give it your all.”

- Focusing on approval from others: As the coach, you could use Sara’s desire for approval from the coach, teammates, or others to motivate her. This creates a sense of duty to live up to others' expectations.

- Example: “Your teammates look up to you and count on you to set an example. You wouldn’t want to let them down by not putting in your best effort.”

- Invoking shame or pride: As the coach, you might try to make Sara feel that her self-worth is tied to her performance, pushing her to act out of a desire to avoid shame or gain pride.

- Example: “You’re a strong rower, Sara. Imagine how disappointed you’d feel if you didn’t push yourself to maintain that reputation.”

- Creating comparisons to reinforce self-image: As the coach, you might compare Sara to other athletes, encouraging her to uphold a certain standard to maintain her self-image as a dedicated rower.

- Example: “You’re one of the hardest-working athletes on the team. You wouldn’t want to lose that edge or fall behind others, would you?”

- Using self-comparison for motivation: As the coach, you might motivate Sarah by comparing her performance to past achievements, encouraging her to match or surpass her own previous results. This leverages her desire to avoid the feeling of underperforming compared to her personal best and keeps her striving for improvement.

- Example: “Last season, you set a new personal record in that event. I know you can reach that level again, and it would be disappointing if you didn’t push yourself to maintain or beat it this year.”

In all of these examples, the motivation stems from Sara’s internal sense of duty, guilt, or the desire for validation rather than pure intrinsic enjoyment of rowing. While introjection might be effective in the short term, it can also lead to burnout or stress, as the motivation is based on avoiding negative emotions rather than fostering internal satisfaction or personal alignment with the activity.

Reflect on your leadership:

As a leader, sometimes you need to tap into your team’s internal pressures—whether it’s a sense of duty, guilt, or the need for approval. Introjected regulation can be a short-term tool to keep people motivated, especially when they need a little extra push to meet responsibilities. However, it’s important to walk that fine line between motivation and burnout. You’re not just reminding them of their tasks, but appealing to their sense of pride and the internal drive to avoid letting others down. While useful, relying too much on this can lead to stress and fatigue, so it’s crucial to balance this approach with positive reinforcements.

Think about the questions below, or journal them:

- How might leveraging your team’s sense of duty or internal pressure help you motivate them in the short term? What impact could this approach have on your leadership style?

- What risks or challenges could arise from relying too heavily on introjected regulation, and how can you ensure you’re supporting your team without pushing them toward burnout or guilt-driven fatigue?

Key Points of Introjected Regulation:

- Introjected regulation occurs when behaviour is motivated by internal pressures such as guilt, shame, or the desire for approval, rather than personal enjoyment or a sense of identity.

- The individual engages in the behaviour to maintain self-worth, avoid negative feelings, or meet external expectations, making the motivation feel somewhat controlling.

- This type of motivation is extrinsic, driven by the need to avoid internal discomfort, rather than the behaviour being aligned with the individual’s core values or long-term goals.

- While effective in the short term, introjected regulation can lead to stress and burnout if relied on too heavily, as the motivation stems from avoiding negative emotions rather than fostering personal fulfillment.

External Regulation (Rewards, Punishments)

Occasionally, Sara’s club holds competitive challenges where small prizes are awarded. Though these aren’t her primary motivation, she enjoys the friendly competition and the rewards that come with it. Her coach ensures that external rewards are used sparingly and in a way that aligns with the team's values.

- Competence: These external incentives help Sara see her improvements in concrete terms. Positive feedback and small external rewards boost her competence.

External Regulation:

- External regulation is the most controlled form of extrinsic motivation. It refers to behaviour that is driven entirely by external rewards, punishments, or pressures. The individual’s actions are motivated by external forces, such as tangible rewards or avoidance of punishment, rather than any internal desire or personal value.

External regulation is like the drill sergeant of motivation—it’s all about rewards and punishments, with zero internal connection. In this case, the coach isn’t tapping into any deep personal values or goals; they’re using carrots and sticks to get Sara moving. It’s the most controlled form of extrinsic motivation in Self-Determination Theory (SDT), where her behaviour is driven by external consequences.

Sara’s rowing not because she’s found meaning in it, but because she’s aiming to gain a reward or avoid some sort of penalty. It’s the difference between doing something because you want to and doing it because you have to. It works, but only as long as those rewards or punishments are on the table. There’s no deeper connection, just action based on what happens if you succeed—or what you’re trying to dodge if you don’t.

You as the coach?

Now, imagine yourself as the leader using external regulation to motivate your team. This is all about the carrot and stick approach—motivating them with rewards or consequences. You’re saying, “Hit this target, and there’s a bonus in it for you,” or “Miss this deadline, and we’ll need to have a serious chat.” It’s straightforward and effective when you need quick results, but it’s very much about the short-term gain. As the leader, you’re driving action with external motivators—whether it’s recognition, financial incentives, or avoiding penalties. It gets things done, but be careful: if you rely too much on this, your team will only move when there’s a reward or a consequence dangling in front of them. It’s a decent tool, but not one you want to pull out for every job.

Ways a coach might use external regulation to motivate Sara:

- Offering rewards: As the coach, you could promise Sara tangible rewards, such as prizes, recognition, or other benefits for meeting specific performance goals.

- Example: “If you row under 2 minutes per 500 meters today, you’ll win a gift card to your favourite coffee spot.”

- Threatening punishment: As the coach, you could use the threat of negative consequences, like extra training sessions, being benched, or losing privileges, to push Sara to perform.

- Example: “If you miss practice or don’t meet your time goals, you’ll have to do extra conditioning drills.”

- Promising external validation: As the coach, you might motivate Sara by promising public praise, awards, or recognition in front of her peers, appealing to her desire for external validation.

- Example: “If you improve your time, you’ll be recognized as the most improved rower on the team at the end-of-season banquet.”

- Using competition or comparison: As the coach, you could create external pressure by comparing Sara to others and emphasizing how outperforming her peers will bring rewards or status.

- Example: “Beat your teammate's time, and you’ll get to row in the top boat for the next race.”

- Financial or material incentives: As the coach, you might offer Sara money, gear, or other material rewards based on her performance or attendance at practice.

- Example: “If you make it to the national championships, you’ll get a new set of rowing gear.”

Reflect on your leadership:

As a leader, external regulation—using rewards and consequences—can be a powerful tool for driving quick results. But it’s important to recognize that this method taps into short-term motivation. You’re motivating people with tangible outcomes rather than internal fulfillment or personal growth. External rewards can get the job done when deadlines are tight or when you need to boost performance quickly, but be careful not to rely on this too often. If your team only moves when there’s a carrot or a stick, you risk creating a culture where long-term engagement and deeper satisfaction are absent. Balance is key—using external regulation strategically while fostering more intrinsic connections will help build a sustainable, motivated team.

Think about the questions below, or journal them:

- What external rewards and punishments have worked best for you in the past? How can using external rewards or consequences motivate your team in a way that supports short-term performance that is authentic to you without creating an environment where the people you lead are dependent on external incentives?

- What strategies can you implement to systematize external regulation in your organization? Can you do this while helping your team find deeper purpose and engagement in their work?

Key Points of External Regulation:

- The focus is entirely on external consequences—what Sara can gain or avoid.

- Motivation depends on external factors and often requires continuous rewards or threats to maintain.

- External regulation can lead to compliance but may not foster a genuine commitment to the activity itself, as Sara is doing it for external rewards rather than any internal connection to rowing.

While external regulation can be effective in the short term, it often lacks sustainability. Once the external rewards or punishments are removed, Sara may lose her motivation since she hasn’t internalized the reasons for her actions.

Amotivation (No Intention)

Sara rarely feels amotivated because her environment constantly supports her. However, during a short injury, she struggled with apathy, unsure if she could get back to where she was. Her coach addressed this by giving her small, manageable goals to rebuild her confidence, preventing her from falling into long-term amotivation.

In Self-Determination Theory (SDT), amotivation is like standing at the edge of a motivational cliff—completely disengaged, staring into the void, and wondering why you’re even bothering. It’s not just about feeling lazy or unenthused; it’s a deep sense of apathy, where a person has zero drive to engage in the task at hand. They’ve lost any sense of purpose or value in what they’re doing. Maybe they feel like their actions won’t lead to any real outcome, or they’re convinced they don’t have the skills to succeed. Worse, they might feel like they’re not in control, like the work they’re doing is dictated by forces outside of them with no chance to change the outcome. Whatever the cause, they’ve hit the wall where motivation just doesn’t live anymore.

Amotivation sits at the far end of the motivation spectrum, way beyond just not feeling like it today. It’s the point where someone has mentally and emotionally checked out. Their actions feel pointless, and even if they’re going through the motions, there’s no intention behind it. No reward is tempting enough, and no punishment is scary enough to get them to truly engage. Whether it’s because they can’t see the bigger picture, don’t believe in their ability to succeed, or feel totally powerless, amotivation is the state where they’re left asking themselves, “What’s the point?”—and that’s the exact question you, as a leader, need to help them answer.

You as the coach?

Now, picture yourself as the leader dealing with non-regulation, where someone on your team is going through the motions without motivation or real intention. This is the “checking out” zone, where they don’t see the point in their work, and it’s all starting to feel like a chore. As a leader, your job here is to reignite the spark. It’s about having honest conversations to uncover what’s going on—what’s causing this apathy? You’ll need to break things down into small, achievable steps to help them see progress again and find meaning in what they’re doing. Maybe it’s about helping them connect their role to something bigger, or simply rebuilding their confidence by focusing on small wins. It’s not about forcing motivation—it’s about guiding them back to finding purpose and reminding them why they started in the first place. Your role is to help them move from disengagement to re-engagement, one step at a time.

Ways a Coach Might Address Amotivation in Sara:

- Addressing Impersonal Apathy: Sara may feel completely disconnected from rowing, feeling that no matter what she does, it won’t make a difference. This could be because she doesn’t see her personal contribution as valuable or because she doesn’t feel capable of improving.

- Coach’s Strategy: As the coach, you can have a one-on-one conversation to dig deeper into why Sara feels this way. Perhaps she feels overshadowed by stronger teammates or struggles with a skill. The coach might focus on small, achievable goals to rebuild her confidence.

- Example: “Sara, I know it feels overwhelming right now, but let's focus on one thing at a time. What if we work on your stroke technique this week? By the end of the week, I guarantee you’ll see improvement. You’ve got this.”

- Lack of Confidence or Perceived Competence: Sara might feel like no matter how hard she tries, she won’t improve. This is a common cause of amotivation—when an individual doesn’t believe they have the competence to succeed.

- Coach’s Strategy: As the coach, you could break down the tasks into manageable pieces, providing positive reinforcement for small improvements to build Sara’s sense of competence. Regular feedback and celebrating small wins can help her see that progress is possible.

- Example: “Let’s take it step by step. Today, we’ll focus just on your start. Don’t worry about anything else. I’m sure you’ll see progress, and that’s a win.”

- Lack of Connection to Outcome (Effort Won’t Matter): Sara might believe that her efforts in rowing don’t lead to meaningful outcomes. She feels her contribution doesn’t affect the overall success of the team or that rowing won’t benefit her in the long run.

- Coach’s Strategy: As the coach, you can emphasize the direct link between Sara’s efforts and results, both for her personal growth and the team’s success. By showing Sara how her contribution matters, the coach can help her regain a sense of purpose.

- Example: “When you focus on improving your timing, the whole boat moves more smoothly. Your effort really does make a difference to the team’s success.”

- Feeling Controlled or Lack of Autonomy: If Sara feels she has no say in how she trains or what her goals are, she may disengage and become amotivated. A lack of autonomy can lead to a sense that she’s just going through the motions without any personal investment.

- Coach’s Strategy: As the coach, you could involve Sara more in her training decisions, allowing her to have some say in how she approaches practices. This helps restore her sense of autonomy and ownership over her progress.

- Example: “Sara, how would you like to approach the next few weeks of training? We can adapt the schedule to what you think will work best for you.”

- No Personal Interest or Value in the Activity: Sara might not see the point of rowing because it doesn’t align with her personal interests or goals. This disconnect between the activity and her values can lead to amotivation, where she feels no intrinsic or extrinsic reason to continue.

- Coach’s Strategy: The coach can explore what Sara does care about and help her see how rowing might connect to those values or interests. This involves identifying what’s meaningful to her and framing rowing as a way to fulfill those deeper desires.

- Example: “You’ve told me how much you value pushing yourself and growing mentally. Rowing is a way for you to achieve that—it’s not just about being in the boat, it’s about what you’re gaining from every challenge you face here.”

Reflect on your leadership:

As a leader, one of your toughest challenges is addressing amotivation—when someone on your team has lost their drive, checked out mentally, and feels disconnected from their work. You’ll know it when you see it—tasks feel meaningless, and no amount of external reward or consequence seems to move the needle. Your role in these moments isn’t to push harder, but to reignite the spark. It’s about getting to the root of their apathy through honest conversations and understanding what’s causing them to disengage. You’ll need to help them break down the overwhelming feelings and find small, manageable steps to rebuild their confidence and sense of purpose. Think of it as guiding them back to their “why,” one conversation, one small win at a time. It’s not about forcing motivation—it’s about helping them rediscover meaning.

Think about the questions below, or journal them:

- How might having honest, open conversations with disengaged team members help you as a leader better understand their challenges and re-engage them with a sense of purpose? What insights could you gain from these moments of connection?

- What benefits could you experience as a leader by breaking down overwhelming tasks into smaller, achievable steps to rebuild your team’s confidence and momentum? How could this approach enhance your leadership effectiveness and foster greater team resilience?

Key Points of Amotivation:

- Amotivation is a state of complete disengagement, where the individual sees no value or point in the activity.

- It often arises from a sense of impersonal apathy, where the individual doesn’t feel competent, doesn’t believe their efforts matter, or feels controlled and disconnected from the task.

- Addressing amotivation requires helping the individual regain a sense of competence, autonomy, and relatedness to the activity, as well as connecting the activity to their personal values or goals.

Conclusion

Sara thrives because her basic psychological needs for relatedness, competence, and autonomy are continually supported. Her coach and teammates foster an environment where motivation is nurtured and allowed to grow. Over time, her motivation has evolved from external rewards to something much deeper—intrinsic motivation. Whether she’s striving for personal growth, contributing to her team’s success, or simply enjoying the flow of rowing, Sara’s sense of purpose and meaning is ever-present.

Maggie, on the other hand, is stuck in a cycle of amotivation. Her club’s overemphasis on external rewards and punishments, combined with a lack of feedback and connection, leaves her feeling isolated and controlled. Instead of building her competence and autonomy, the environment suppresses it. Maggie, who once had the potential for greatness, now feels demotivated and disconnected from her values and the joy of the sport.

The difference between Sara and Maggie lies in how their environments shape their motivation. With the right support, motivation can evolve into a powerful force that fuels not just performance but personal fulfillment. Without it, even the most promising individuals can become disengaged.

But motivation isn’t limited to the world of sports. In fact, the same principles apply in all areas of life—including the construction site. Next up, we’ll explore Mike’s story and see how these theories play out in a completely different setting. Get ready to see how motivation works in the rough-and-tumble world of construction and what leaders can do to keep their teams firing on all cylinders!

Story of Workplace Transformation: Mike Learns From Sara & Maggie

Mike had just taken over as the new site manager for ACE Engineering & Construction, a mid-sized firm where morale was as low as the last quarter’s earnings. The crew was burned out, performance was slumping, and motivation? Well, it was buried somewhere under the rubble. The company had been through more management changes than a game of musical chairs, and the team—made up of long-term employees and unionized workers who were practically bulletproof—was fed up. Criticism was the name of the game, and tempers flared faster than a faulty blowtorch. The old foreman had ruled with an iron fist, but Mike knew that wasn’t going to cut it anymore.

Mike himself was no stranger to tough situations. He wasn’t the kind of leader to sugarcoat things or rely on fancy speeches. Years of working in construction had shaped him into a straightforward, get-it-done type of guy. His leadership style was built on trust, respect, and accountability, but Mike knew there was more to leadership than just barking orders. He valued hard work, but he also understood that people needed the right kind of support to truly thrive. Mike had seen firsthand how fostering autonomy and growth could transform people, and while he wasn’t the most talkative boss, he was deeply committed to building a team that could take ownership of their work and excel. This was a new chapter for ACE, and Mike wasn’t going to lead the same way as his predecessors.

Mike wasn’t your average construction boss. For starters, he had a secret weapon—his family. You see, Mike was married to Sarah, and Maggie was his sister-in-law. From watching both of their journeys in the world of rowing, Mike had learned a thing or two about motivation, leadership, and what happens when you get it all wrong. Sarah thrived in an environment where her basic psychological needs—relatedness, competence, and autonomy—were met, and she had blossomed into a top performer. Maggie, on the other hand, had crumbled under a system of rewards, punishments, and lack of support, becoming a shadow of her potential. Mike had seen the best and the worst of motivation in action, and he wasn’t about to repeat Maggie’s story at ACE.

So, as Mike took the reins at ACE, he made a decision: no more caveman leadership. Instead, he’d lean into Self-Determination Theory (SDT), just like Sarah’s coach had done on the water. He wanted to build an environment where his crew felt connected, capable, and in control of their work. Not an easy task in the rough-and-tumble world of construction, where barking orders and cracking the whip was the norm. He knew emotions and tempers would still flare, but Mike was ready to flip the script.

He focused on building relatedness—finding common ground with the crew, getting to know their stories, and showing them that their contributions mattered beyond the paycheck. Then, he targeted competence, giving the team the training and feedback they needed to improve, but in a way that built confidence, not resentment. And lastly, he gave them autonomy—letting them have a say in how projects were approached, empowering them to take ownership of their work rather than just following orders.

The culture shift wasn’t overnight—Mike knew better than to expect a quick fix. But slowly, things started to change. Tempers cooled, and the criticism dialed down. Workers started taking pride in what they did, and performance started creeping back up. And while ACE wasn’t winning any "Best Place to Work" awards just yet, the gears were turning, and the team was getting back on track. Mike’s approach wasn’t just a theory—it was a practical, boots-on-the-ground application of what happens when you understand human motivation.

Now, buckle up, because Mike’s story at ACE Engineering is just getting started. We’re about to dig into how this approach, rooted in Self-Determination Theory, plays out in a gritty, hard-edged industry. Mike's using what he’s learned from Sarah and Maggie, and you’re about to see the payoff firsthand. Let's jump into the action and see how motivation works in the world of heavy machinery, deadlines, and construction site challenges!

The Old Environment: Like Maggie’s Rowing Club

Amotivation and External Regulation

At ACE, most crew members were just there for the paycheck and punching the clock. Whether it was the engineers hunched over their computers or the laborers swinging hammers, the job was just that—a job. They were there for the paycheck, and that’s about where their motivation ended. They’d clock in, do the bare minimum to keep the wheels turning, and clock out without giving a second thought to how their work fit into the bigger picture. The passion for the craft? Buried somewhere under the dust and debris.

Motivation came almost entirely from external regulation—meet the deadlines or face angry clients. The project managers only got involved when something went wrong, and they spent more time blaming others than fixing problems. People were working to avoid Mike’s anger, and the few positive incentives—like bonuses—weren’t enough to drive real engagement. The whole place was running on autopilot, and it wasn’t pretty.

Introjected Regulation

For those who did care about doing a good job, it often came from a sense of obligation rather than any real passion. The site supervisors, in particular, felt immense pressure to meet deadlines and avoid getting blamed for mistakes. They didn’t want to look incompetent in front of the crew, so they pushed themselves, but there was no real joy in it. The constant fear of criticism created tension throughout the firm.

Lack of Relatedness, Competence, and Autonomy

- Relatedness: The team felt disconnected. The office staff barely communicated with the site teams, and there was a clear divide between the blue-collar laborers and the engineers. The environment was cutthroat, and backbiting was common.

- Competence: Very few workers felt like they were improving or growing in their roles. Engineers were often stuck with repetitive tasks, and the construction teams didn’t receive any real feedback except when things went wrong.

- Autonomy: Workers felt they had no say in how the projects were run. They were told what to do, how to do it, and were expected to stick to the plan—no questions asked.

Reflect on your leadership:

As a leader, it’s easy to fall into the trap of running things on autopilot—where people show up for a paycheck, do the minimum, and then leave without a second thought. At ACE, the crew’s motivation came from fear of missing deadlines or avoiding angry clients, not from any real connection to the work. They were operating out of external regulation, and the few who did push themselves were driven more by a sense of obligation than passion. There was no joy, no ownership, and certainly no real growth. As a leader, it’s crucial to recognize when your team is running in this kind of environment, where blame is more common than support, and where people feel isolated from their peers.

Take a moment to reflect on the environment you’re creating for your team. Is it one where relatedness, competence, and autonomy are lacking? Are your people connected to each other and the mission, or are they just clocking in and out? How can you shift from a culture of fear and obligation to one where people feel empowered, supported, and motivated to grow?

Think about the questions below, or journal them: